Ana Carolina de Assis Nunes describes a community’s resistance to a Google data center in Oregon, examining the longer histories of logging and extraction that shaped the city of The Dalles.

Arts of Noticing: Extractive Stories About the Columbia River

The Cloud is Dead: A Series on Living with Legacies of Resource Extraction

By Ana Carolina de Assis Nunes

April 21, 2025

In the late summer last year, I was walking my dogs on the Riverfront Trail in the city of The Dalles, Oregon. I was in town to conduct some fieldwork for my PhD research that focuses on Google’s data center presence in the city — and more specifically, on what is happening at the intersection of technology, environment, and society in this place that has such a rich history of industrial development and resource extraction.

Even when my dogs weren’t with me, I still enjoyed strolling on the paved area along the gorge at the end of the day. When I took the below picture of my “research assistants,” the day was particularly rainy and the town, which sometimes reminds me of the setting of a western movie, seemed even emptier and sadder, in stark contrast to the vivacity of old times as expressed in the signs and commemorative plaques strategically placed in the touristic area.

The Dalles is surrounded by the beautiful Cascade Mountain Range, which is inescapable from any point in the city — or at least that’s my impression, as someone who comes from a plateau region in Brazil and is not used to such landscapes. This idyllic scenario, and the concrete path along the Columbia Gorge, usually transports me to a mental space of peace and calm. But there’s more beyond the surface. As Anna Tsing admonishes us, in order to see “we must reorient our attention” and “look around rather than ahead.”

The author’s research assistants. All images by Ana Carolina de Assis Nunes.

A saloon in the city of The Dalles, reminiscent of a movie set in the wild west.

As I contemplated the river and the mountains surrounding it, I thought about a particular way this river has been framed over time. Official information, like what you’ll find when you visit the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center and Museum, tends to describe the Columbia River — “the great river of the west” — in terms of its strong waters. So strong, in fact, that the river burst a glacial dam at the end of Ice Age Floods, some 18,000-15,000 years ago, forcing the release of its waters through several states until it reached the Pacific Ocean, forever reshaping the geology and landscapes of the Pacific Northwest. This official narrative also states that the source of the Columbia River is the Columbia Lake, in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, and that the river drops about 2,650 feet from its source to its sea-level mouth near Astoria, Oregon. This sudden drop in altitude, according to historian Paul C. Pitzer, makes this location perfectly suited to host hydroelectric and irrigation projects.

But origin stories are difficult to tell. Do the Columbia waters actually come from the Columbia Lake, or from the rain? Historian Richard White writes that “as the clouds cool, the moisture falls as rain,” filling the river with abundant water; that “without solar energy to move the water inland and uphill, rivers would never begin; without gravity to propel the water downhill back toward the ocean, rivers would never flow.” But while White presents this holistic story about the formation and existence of the Columbia River, he goes on to describe the river as an “organic machine” — meaning that he perceives it as an energy system, modified by human interventions while maintaining its “unmade” qualities. Because of this, “the river demanded energy to match its energy,” White writes, later acknowledging the importance of machines to the western imagination in the nineteenth century, with mechanization marking the modern and nature representing the past. Ultimately White argues that “the organic and the mechanical” have been merged in the Columbia: “the river is not gone; it is our hopes for it that have vanished,” he concludes.

Humanities scholars from multiple disciplines have written about the artificial divide between nature and culture — that is not what I’m trying to do here. Instead, I mention the official story about the formation of the Columbia River (the one told by the city of The Dalles and the state of Oregon) and an important source of historiographic information about that river (via one academically acclaimed book) to shed some light on how, over time, understandings of the river as strong and machine-like have contributed to its current state of degradation. At a glance, that degradation can be imperceptible, until you reorient your attention and look around.

Part of the Columbia River Gorge.

As my PhD research shows, the industrial development of the Columbia River has its roots in the construction of hydropower plants in the 1930s. According to researcher Roberta Ulrich, the construction of federal hydroelectric dams like the Bonneville Dam (1938) and The Dalles Dam (1957) initiated a wave of dam construction along the river in such a dramatic way, that today, only 57 of the river’s 1,249 miles remain free-flowing. Over time, these hydroelectric projects have produced cheap electricity, which in turn has attracted energy-intensive business to the area, such as the data center industry. In the past, such industries included aluminum smelting and even a nuclear facility.

The industrialization of the Columbia Gorge has been so well incorporated into the current architecture of the city, that the impression is the big warehouses have always been there — much like the ever-present Cascades. But when you reorient your attention, you start to consider that Google’s data center, which has been in operation since 2006, occupies a space that was occupied by an aluminum smelting company during the years 1958-1987.

When Google built its first data center in The Dalles in 2006, it received tax breaks from the local government worth at least $260 million dollars. Since the company began its operations in the city, it has refused to share information about its water usage — it only released that information after The Oregonian won a legal battle after 13 months in court. With its release, we learned that yearly, the company’s data center consumes more than a quarter of all the water used in the city. In 2023, The Dalles negotiated a new water rights agreement with Google, and the company had to pay for an upgrade to the city’s water system. The company is currently expanding its location in the city.

Google’s data center in The Dalles.

As invisible or enduring as many industries seem to be along the Columbia Gorge, the river was once the most radioactive in the world. Anthropologist Shannon Cram has documented the process of cleaning the river of the radioactive waste that was dumped and leaked into it in the context of plutonium production in the Hanford Nuclear Facility, up in the city of Richland, Washington, towards the end of the 40 years in which Hanford operated its nuclear reactors at full capacity.

Today, we’re hearing more talk about the production and use of nuclear energy to power data centers, due to the electrical demands of such facilities. Though nuclear energy and nuclear weapons are two different things, they both generate waste, and are both dangerous in a place like Oregon, where the Cascadia Subduction Zone means residents conduct earthquake drills every year in preparation for the big one: a 9.0 earthquake on the Richter scale, long overdue. But the river, and the entire region that was once used “as a vast sink into which engineers could dispose of hundreds of thousands and eventually billions of gallons of radioactive and toxic waste” has had other meanings for different groups over time.

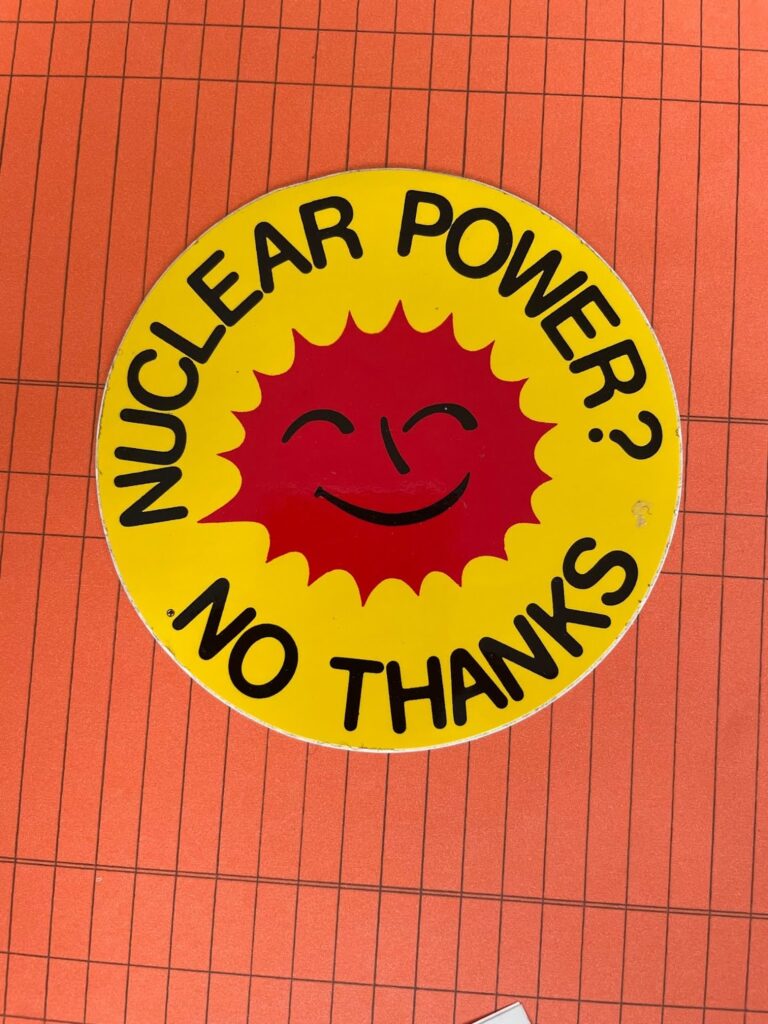

The smiling sun is an international symbol of the anti-nuclear movement. I found this sticker during one of my visits to the special archives collection at Oregon State University, where they keep a collection on the history of atomic energy.

In my many conversations with people who care about the river as more than a resource to be extracted, there is a clamor for a different way of understanding it: a view somewhat akin to what anthropologist Marisol de la Cadena calls “earth-beings,” other-than-human beings that participate and are in mutual relationships of care with a group of people in its surroundings. What might change if we reorient our attention, and look around rather than ahead? What might happen if we learn to think about the ways the Columbia River has been part of the lives of many people over the course of its existence?

“Water has always been a friend of mine in all of her forms, and especially as she traverses along the landscape with all of her power, connecting places across time – connecting me to my Ancestors,” writes Emma Jonhson in Voices of the River, a collection of stories about the Columbia River. I want to invite you to start conceiving the waters of the many rivers in the country in such a manner — as earth-beings, replete with stories and embedded in many narratives, not only the one of progress and brute-force. As data centers try to find ways to cool servers with less energy, and work around the clock to promote a green image, let’s not forget that the cloud — which is not a cloud at all, but a network of hard-drives, servers, routers, fiber-optic cables — is also contributing to the climate crisis.

Ana Carolina de Assis Nunes is a PhD candidate in anthropology at Oregon State University, producing knowledge at the intersection of anthropology and science and technology studies (STS). Her research explores industrial practices in the Columbia River in Oregon since the 1930s, culminating with the recent presence of data centers in the region.