In his essay for our series “The Cloud is Dead,” D&S affiliate Zane Griffin Talley Cooper examines resource extraction in the Arctic and how fantasies of the Network State run counter to the reality of life in Greenland.

The Network State and Topological Fetishism in Greenland

The Cloud is Dead: A Series on Living with Legacies of Resource Extraction

April 21, 2025

The polar sun circles low above the horizon, stretching shadows like dough. I am sitting on an outcropping of ancient rock overlooking the Upernaviarsuk Agricultural Research Station, about thirty minutes east of Qaqortoq, South Greenland’s largest town. Upernaviarsuk is part of the larger Kujataa Unesco World Heritage Site, an area that extends across the Tunulliarfik Fjord, containing the island’s best-preserved Norse ruins, some of South Greenland’s most verdant pastureland, and numerous towns and settlements — including the storied villages of Qassiarsuk and Igaliku, where Erik the Red first established a Norse presence upon his exile from Iceland in 982 AD. The farm is owned and operated by the Greenlandic government as a research station tasked with innovating new approaches to agriculture and animal husbandry in sub-Arctic regions. On this small island, rolling hills of low grasses and blossoming shrubbery are peppered with tilled fields and greenhouses; dozens of sheep graze in the distance. In these fields, agricultural researchers breed Arctic-hardened varieties of lettuce, cabbage, potatoes; and in the greenhouses, tomatoes, berries, and other vegetables. This research station also provides most of Greenland’s Christmas tree crop each year.

Overlooking Upernaviarsuk. Photo by Zane Griffin Talley Cooper

Upernaviarsuk is an endeavor by Greenland’s government to better understand and utilize the possibilities of the land to support domestic food production and build a stronger Greenlandic culinary identity. But it is far from the only agricultural area in Greenland. If you know where and how to look, agriculture is everywhere in South Greenland. It defines the topography. Flying into the Narsarsuaq airport, you can see this agricultural topography stretched across open fields and tucked in valleys between cascading spires of black granite. Taken together, the broader Kujataa region, a comparatively small sub-Arctic enclave at the southwestern edge of the sweating ice sheet, is quite literally the breadbasket for 58,000 people. Some of the food grown at Upernaviarsuk travels an hour north to the Inuili Food College in Narsaq, where students learn to master local culinary traditions. Also in Narsaq sits the Neqi slaughterhouse, the town’s largest employer, where all of Greenland’s lamb, musk-ox, and reindeer meat is prepared, packaged, and shipped across the country. Every August, Narsaq springs to life as over forty sheep farms from all over South Greenland round up their flocks and descend on the town for the annual Sheep Farmer Festival, where sheep often outnumber residents three to one. If we keep venturing North from Narsaq across the fjord, we find a large potato farm tucked inside a microclimate at the base of a glacier. These potatoes, sometimes fifty tons a season, populate grocery stores and restaurants across the country. Greenland indeed!

Elsewhere, thousands of miles from Kujataa, Dryden Brown — former competitive surfer and college dropout from Santa Barbara — waxes poetic on X about his plans to buy Greenland and establish a utopian Network City-State there called Praxis Nation. Over the last six years, Brown has raised hundreds of millions of dollars from venture capital firms throughout Silicon Valley (notably the Peter Thiel-backed Pronomos Capital) to make Praxis a reality. The city would become the physical manifestation of what is called a Network State — a hypothetical form of digital governance underwritten by crypto, AI, and a whole basket of tech imaginaries. The Network State model seeks to eschew most forms of social and environmental regulation, instead promoting a libertarian fantasy of rapid privatized innovation and development. Praxis previously toyed with the idea of building its city “somewhere in the Mediterranean,” but pivoted to Greenland in 2019, the first time Donald Trump floated the idea of buying it.

The aesthetics of Greenland suit Brown’s agenda because the island has long played the part of the harsh frontier, and has been topologically fetishized as both the edge of the world and a land of mystery and plenty by countless Europeans throughout the centuries. Last year, Brown spent a week in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, satisfying his growing fetish for building his city at the end of the world. While in Nuuk, when he wasn’t polar-plunging into the bay (according to him it was “extremely cold, but awesome”), he claims he spent time meeting with various political and industry leaders, including members of Inatsisartut (Parliament). Nuuk may be cold, but it is not a frontier, nor the edge of the world. It is a city of 20,000 people with a large mall, great Thai food, and a modern, opulent cultural center where I saw Top Gun: Maverick; after a week there, Brown described Greenland as “hardcore” and “an actual frontier” that “can serve as a sandbox for terraformation experiments, funded by realizing its potential as a mining and industrial hub.” Yet, while braving this frontier, Brown and his fellow Praxians stayed at the HHE Express, a budget version of the nearby Hotel Hans Egede, Nuuk’s premier four-star hotel. Perhaps they ate at the Sarfalik Restaurant on the top floor, the same restaurant where Donald Trump Jr. paid a group of panhandlers to come to lunch and pose as MAGA supporters. In subsequent threads on X, Brown lays out his plans to “build an urban development for the pioneers that pursue opportunities in Greenland,” and “prototype terraforming solutions to improve extreme, harsh conditions, potentially to be used off-world.” He also flirts with AI-generated ideas of building a “frontier AI research lab,” and invading Greenland with the “Praxis Liberation Army.”

Notably, nearly every piece of imagery associated with these fantasies is AI-generated, while actual photos of Brown’s activities in Greenland are comparatively sparse. AI and its associated imaginaries (Web3/crypto, the TESCREAL bundle, the Network State, etc.) are all topological fetishes inherently antithetical to the topographical realities of our lived environment. Land is both a physical and affective thing — an embodied experience built through ongoing relations with environments. Land is not topological; it is topographical, with ridges, edges, canyons, and mountains. And despite having an outsized impact on global topography, the tech industry increasingly defines itself through its fetish for the topological, a flat binary imaginary free from the constraints of the worldly. Closer now to religion than a functional sociotechnical system, today’s tech landscape overflows with twisted ideas for chrome-washed, eugenic futures (often under the guise of sustainability) and champions a mutated, lazy iteration of Manifest Destiny (Brown calls it a “new Monroe Doctrine”) completely disconnected from any sort of social or ecological reality. These myriad experimental approaches to this new digital sovereignty are most firmly crystallized in the Network State, a concept that holds that the form and function of the state are not determined by geography, but rather by code. This does not mean that a Network State cannot have geography, but that geography does not define its contours. While its biggest champions like Peter Thiel and Balaji Srinivasan have specific visions for building on and across actual geographies, the idea of the Network State simultaneously maintains a critical distance from land. It is a financialized state, able to rapidly ravage, exploit, and exit any geography that might resist its strange, feudal forms. Buttressed by “techno-colonial imaginar[ies]…frontier self-determinism, and digital nomadism,” the politics of exit are at the conceptual core of the Network State. It owes nothing to anyone except itself, is beholden to no land, and exists only insofar as it can be coded.

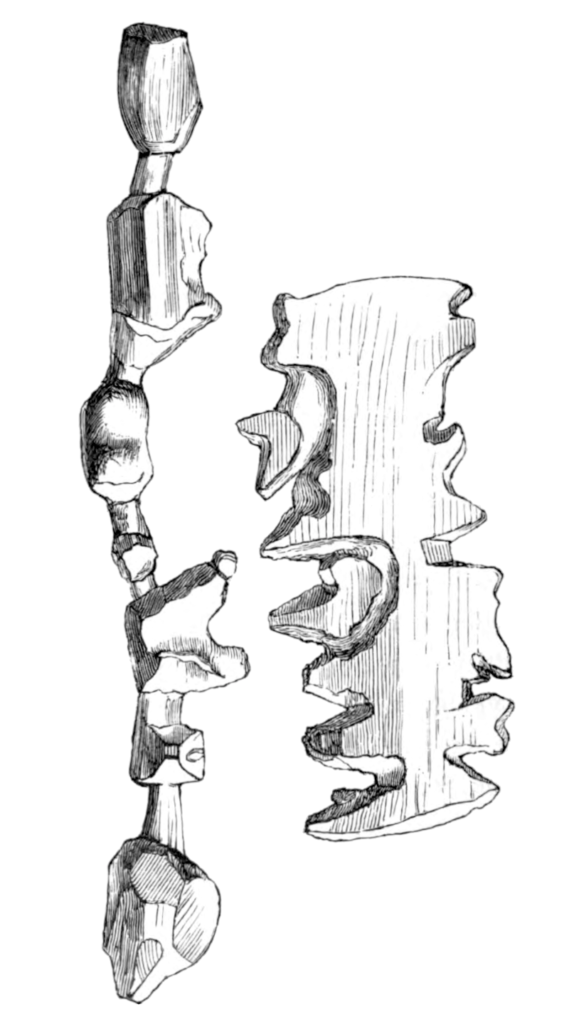

Wooden maps of the east coast from Gustav Holm’s expedition circa 1883. Source, p. 250.

But land is not code. It can never be code. Topography is felt, not just seen. Some of the oldest maps of Greenland are not visual but tactile. Inuit hunters would carve complex fjords and peninsulas into pieces of driftwood, and feel for their location as they traveled up and down the coast. Anthropologist Tim Ingold describes this particular method of feeling the landscape as wayfaring — a moving through the land instead of across it. We move across our environments every day — in cars, trains, planes, from one point on the map to another. For Ingold, a wayfarer does not travel along a line; they are the line. And this line is not straight, but situated in relation with its surroundings. The gridded topology of European cartography has long imagined Greenland in flat, logistical planes. But this topological imaginary does not accurately reflect the lived topographical experience of Greenland’s deep fjords and corrugated coastlines.

Dryden Brown’s topological fetish for an “eternal city” in Greenland is far from an original idea. Europeans have been imagining utopian city-states in the far north since the Renaissance. In the 15th century, two brothers from Venice produced a series of letters and a map of the Northern Atlantic depicting a harrowing adventure across the greater Arctic. While not included on this initial map, the letters of the Zeno brothers describe their alleged discovery of a miraculous city named Alba in Northeast Greenland. According to the Zenos, Alba was “an educated utopia on an island of plenty,” complete with monks, a monastery, and, somehow, bountiful vegetation. While it is now generally accepted that the brothers’ maps and letters were completely fictional, the idea of Alba persisted in maps and histories through the 17th and into the 18th century. The city appears as any other on Mercator’s 1606 map of the Arctic, and decades later in 1678, historian Rudolff Capel wrote about Alba, describing how the enlightened Albans made use of the plethora of hot springs in the area to cook and heat their homes. According to Capel these hot springs helped maintain a temperate climate, attracting a veritable cornucopia of fish and game to the area. A fantasy for sure, but one that held sway for centuries. Like Dryden Brown’s Praxis Nation, Alba was a topological fetish — an obsessive desire for salvation at the edge of the world. It too held its own politics of exit — exit from plagues, war, and the multitudinous vagaries of Europe. But Alba never existed. In its place stands only ice and rock. Praxis too is a speculative dream, a shell imaginary for financial exploitation and little else. Even if Brown manages to acquire land for this project, the land will resist, because the very ideas of Praxis Nation — and Network States in general — are detached from any sort of topographical reality.

As the polar sun sets over Upernaviarsuk, the greenhouses below reflect its warm glow, blanketing the entire research station in an orange sheen. Sheep scatter in the distance across golden fields, and as I watch them run I think about how, unlike Praxis Nation, Upernaviarsuk is not just a fantasy, but part of an actually existing and actively evolving technological future situated firmly in relation to Greenland’s real social, political, and ecological needs. I went to Greenland to better understand how relationships between technology, energy, and resource extraction are situated and situating across its landscape. At Upernaviarsuk, these relationships become tangible, tactile. The future here can not just be seen; it can be felt — and it feels warm, salient, and situated. Despite its ever-growing energy and resource needs, the obscene topological fetishism of today’s tech industry feels ultimately disconnected from place, as if all its tangles of cables and fields of server farms are merely mirages of its glowing interface. But we know the truth, even if we don’t always want to see it. Just futures for all require interventions and technologies that fit the topography, that build on and complement the social and ecological contours of place. The real tech future isn’t in the cloud, but on land. So be here, in place. Take a step, take another, feel the ground beneath your feet. Now you are a wayfarer, mapping the future.